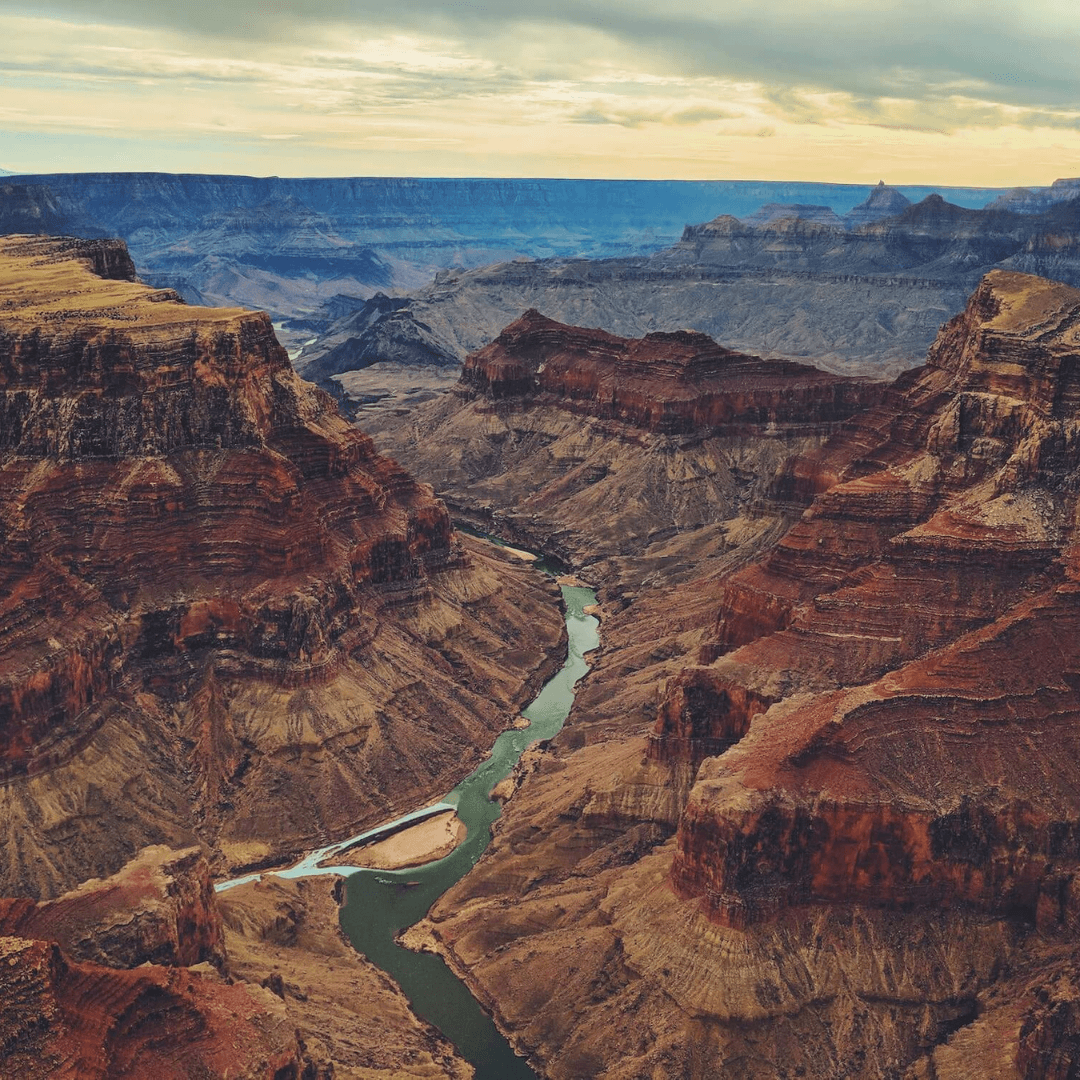

Yosemite. Grand Canyon. Sequoia. Great Smoky Mountains. Zion. Yellowstone.

For some, these names bring nostalgia as memories are recounted of camping trips past, the awe of natural landscapes, or maybe even hope for a future trip. For others, these names seem distant and even elicit feelings of fear and exclusion. Known as “America’s Best Idea”, the national parks saw close to 328 million visits in 2019, and 78% of those who visited were White. While the parks may be open to all, they haven’t always been or felt this way for Black, Indigenous, and/or People of Color (BIPOC), who often report feeling unsafe and unwelcome in park spaces. This is the result of many factors from a history of racism within the parks, to the current lack of representation in park advertisements and staffing. Additionally, many of these parks are difficult to access for those with low-incomes, which only exacerbates their lack of diversity. The differences in how we perceive national parks has a great deal to do with our background and where we come from.

The racist and exclusionary history of the national parks dates back to the very beginning with the removal of Indigenous people. Before the likes of John Muir, Yosemite had residents who were stewards of the land for centuries. In 1850, the Ahwahneechee people who called the Yosemite valley home were forcibly removed during the “Mariposa Battalion” led by Major John Savage. This militia received federal and state government support for their efforts in the “war of extermination” against native people. The Ahwahneechee people were never to return to their homes in the valley, as the area would soon become one of the first national parks. This violent history of the park is often forgotten and overshadowed by John Muir’s legacy. Often touted as the great protector of Yosemite, Muir himself was racist towards Indigenous and Black people. Despite his harmful rhetoric towards BIPOC, if you go to Yosemite today you will see his legacy amplified in trail names and historical landmarks. The original stewards of the land, the Ahwahneechee, only recently had their history featured in the park with a replica village.

Prior to 1964, the national parks were segregated and white-only spaces. That means it’s only been 56 years that BIPOC were allowed full access to the parks. This is within some of our, our parents’, and our grandparents’ lifetimes. This exclusion from the parks has a generational impact on potential visitors. As visits to the parks are often family traditions, for BIPOC these traditions could only begin recently. Addressing this disparity is crucial to the survival of the National Park Service as minorities become the majority of this country. If they fail to rectify their past of exclusion, erasure, and harm of BIPOC, they could lose public support. The parks heavily rely on this support, so if the majority of Americans don’t feel welcome and included in this space they could see massive budget cuts.

Photo from: NPS.gov

If the NPS chose to amplify the history of BIPOC in national parks instead of figures like John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt, they could encourage more diverse people to take pride in these lands. The reason many of the parks look the way they do, is due to Indigenous land stewardship practices. These lands are often touted as “true wilderness” and “untouched”; to the trained eye, these lands had been maintained for centuries to resemble the parks we see today. After the civil war, the 24th Infantry and 9th Cavalry which consisted of 500 Black men, known as the Buffalo Soldiers, became the first park rangers of Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks. Some of their duties included stopping poachers and extinguishing forest fires. This helped lay the blueprint for what would become the current park service. These are only two examples of BIPOC history in parks, but there are more! By enacting monuments to these figures along with sharing the diverse history of national parks, BIPOC people can finally see historical representation in park spaces that has often been forgotten and erased.

While addressing the past is an important part in changing the future, there are other ways the parks could also be more inclusive spaces as well. As touched on earlier, hiring more diverse staff within the parks and featuring more BIPOC in park advertisements are great first steps. This would allow more people to feel welcome and safe in these spaces. As economic accessibility to the parks is a major factor in visitation, offering travel subsidies for low-income families and free first time visitor passes could make these spaces more accessible. This would allow commonly underrepresented groups to forge traditions within the parks and provide positive childhood outdoor experiences, which are known to create a lifelong environmental appreciation. Another way the parks could draw more diverse crowds is by holding cultural events and festivals in and near park spaces. Gatherings of people from different backgrounds to the parks can boost attendance and have the power to lead to a greater appreciation for these areas, as people feel welcome. These are just a few of the ways parks can become more diverse and inclusive spaces moving forward.

While this article mainly discusses the national parks lack of diversity and inclusion, this issue pervades the entire outdoor community. Whether it be outfitters, like Patagonia and REI, or activities like rock climbing, hiking, or camping, there’s a stark lack of diversity in these companies and communities. This does not represent a lack of interest in these activities by BIPOC, but rather the exclusion of them. If you are BIPOC looking for an inclusive outdoor community, here are a few organizations seeking to provide these spaces:

We can all confront the lack of diversity and inclusion in the outdoor community by donating to these organizations. We can also use our voices to hold parks and retailers accountable who aren’t making the necessary efforts to remedy this. As the environment is experienced by everyone, the representation in the parks and outdoor community needs to reflect this as well.

Sources:https://www.theatlantic.com/sponsored/rei-2018/five-ways-to-make-the-outdoors-more-inclusive/3019/

https://www.fs.usda.gov/rmrs/recreating-color-promoting-ethnic-diversity-public-lands

https://www.outsideonline.com/2415467/acp-dapl-keystone-pipeline-protest-wins

https://www.nps.gov/yose/learn/historyculture/buffalo-soldiers.htm